Many don’t live here anymore. Some have passed away. Others simply don’t remember. But half a century later, the Baby Tooth Survey still links thousands of St. Louis area residents who took part.

The study, recalled as one of the great citizen-scientist collaborations, played a part in ending nuclear weapons testing. It also represented a public outreach effort that would be nearly impossible to duplicate, even in today’s world of Facebook and Twitter when information can circle the globe in a fewkeystrokes.

It took 12 years. It involved thousands of school-age children and the collection of some 320,000 tiny teeth. The effort was in search of an answer to one somber question: Was radioactive fallout from atmospheric nuclear weapons testing being absorbed by children in their bones and teeth?

Overwhelmingly, the answer to the question was yes. The study found that children born in St. Louis at the height of the Cold War in 1963 had 50 times as much strontium 90, a radioactive isotope found in bomb fallout and at nuclear reactors, in their teeth as children born in 1950 — before most of the atomic tests. Results ultimately contributed to the signing of an international treaty to ban atmospheric nuclear weapons testing.

To mark the 50th anniversary of the Partial Test Ban Treaty, signed by the United States on Aug. 5, 1963, a New York-based nonprofit research group has organized a panel discussion on the Baby Tooth Survey and its role in history. The event is tonight at 7 p.m. at the Missouri History Museum.

Joseph Mangano, executive director of the group, the Radiation and Public Health Project, said the legacy of the study should not be overlooked.

“It was a factor in speeding the test ban treaty, which to this day was one of the great environmental treaties in history,” he said. “It sort of started the world on the path from inevitable nuclear war and disaster to disarmament.”

The idea for the study was hatched in the mid-1950s during the build up of the Cold War. By then, the U.S. and Soviet Union had tested hundreds of nuclear weapons. Prevailing winds carried the radioactive debris from the U.S. tests, many of which were conducted in the desert regions of the West, to St. Louis and farther east.

As the Baby Tooth Survey later proved, strontium 90 was ending up in pastures and fields, in grass consumed by goats and cows. It worked its way upthe food chain into children’s milk. And because the chemistry of strontium 90 is similar to calcium, it was taken up by bones and teeth.

A group of prominent St. Louis scientists and physicians was concerned about the effects of radioactive fallout from the tests. They lectured to groups across the city, informing the public about isotopes and half-lives, and later formed the Citizens Committee for Nuclear Information.

Founding members of the committee included Eric Reiss’ parents, both physicians. His mother, Louise, was director of the study and authored an article for the journal Science in November 1961. His father, Eric, presented findings in testimony before a Senate committee in support of a treaty.

Today, Reiss lives in Copenhagen. His parents have passed away. At age 59, he still remembers dinner table conversations about cesium and strontium 90. He recalls meetings with scientist and environmental pioneer Barry Commoner and other committee members in the living room of his parents’ large home on Waterman Boulevard. And there was a phone call he took as an 8-year-old in the spring of 1962. At the other end of the line — President John F. Kennedy, asking to speak to his mother.

“It didn’t really even dawn on me at that time that it was the president of the United States,” Reiss said.

All these years later, Reiss said it’s still significant how the Committee for Nuclear Information went about making its point, relying on data, not hyperbole.

“The idea of the Baby Tooth Survey was, ‘Let’s not use emotional argument, let’s use the scientific method to prove or disprove a condition,’” he said.

|

|

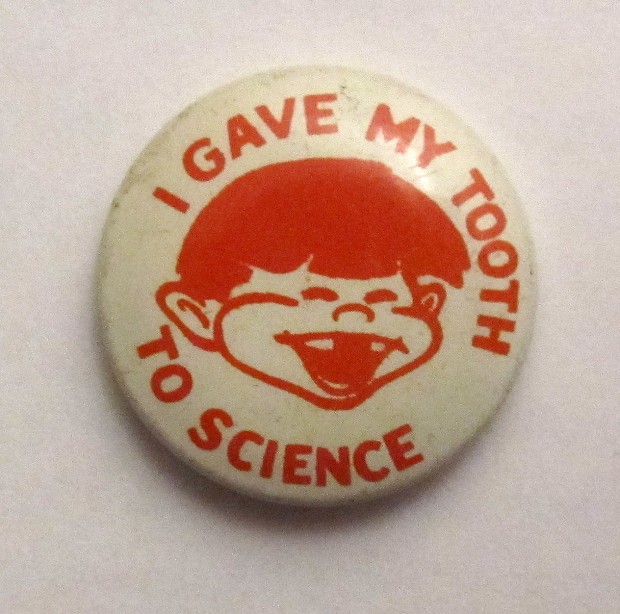

Martha Ackman was among the St. Louis area children who gave up their teeth in exchange for a round metal button featuring a gap-toothed child. She vividly remembers the button, which proudly declared; “I gave my tooth to science.”

Ackman, now a writer and professor of gender studies at Mount Holyoke College in western Massachusetts, grew up in north St. Louis County. Her mother was a nurse at St. John’s Mercy Hospital, and the family was civic-minded and interested in issues dealing with public health.

“It just seemed like a really cool thing to do,” she said. “I don’t remember anything about strontium 90, and I don’t even know if that was vaguely mentioned. To me as a grade-schooler, my family, it seemed like, ‘Let’s help out science and find out something from our baby teeth.’”

Decades later, Ackman had new reason to be interested in the Baby Tooth Survey. While in her 40s, she developed thyroid disease and had a large benign tumor removed. She still wonders if there was a connection between radiation she absorbed as a child and the health effects — a question that will probably never be answered.

SURPRISE DISCOVERY

The Baby Tooth Survey is remembered not only for the results it helped produce, but also because it was a mammoth logistical undertaking.

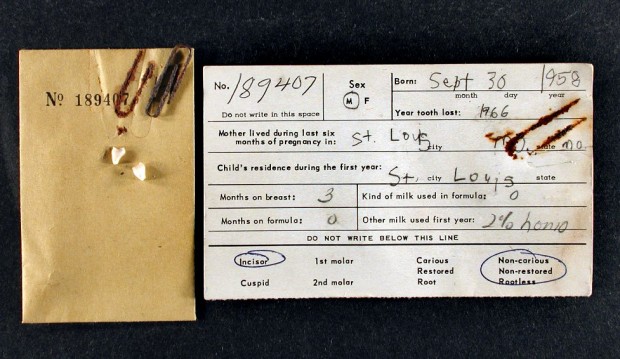

Funded by the U.S. Public Health Service and Leukemia Society of Missouri and Illinois, it entailed volunteers visiting schools, churches and PTA meetings, churches, libraries and dental clinics distributing registration forms. Parents mailed in their children’s baby teeth and information cards with names, addresses, birthdates and other information.

“It was really an amateurish operation, but very idealistic,” said Michael Freidlander, a physicist and professor emeritus at Washington University, who was a member of the Committee for Nuclear Information.

Friedlander, who will be part of Thursday’s panel discussion, wasn’t part of the survey. But his wife was among those who spent evenings sitting around tables, sorting and cataloguing teeth, putting them in envelopes.

|

|

Memories of the Baby Tooth Study faded after it formally ended in 1970.

But a surprise discovery 40 years later revived interest — 85,000 baby teeth in shoeboxes in an ammunition bunker at Washington University’s Tyson Research Center. The teeth, packaged in small envelopes, were among those collected in the 1950s and ’60s but never analyzed for radioactive strontium.

They were given to the Radiation and Public Health Project, which set out to advance the findings of the original study by looking at health effects on people who had elevated strontium 90 levels in their teeth as children.

In 2010, Mangano and Janette Sherman published a study in the International Journal of Health Services. It concluded men who grew up in the St. Louis area in the early 1960s and died of cancer by middle age had more than twice as much strontium 90 in their baby teeth as men born in the same time and area who were still living.

But the study was met with skepticism, even harsh criticism.

Stephen Musolino, a health physicist and specialist in radiation protection at Brookhaven National Laboratory, the Department of Energy lab on Long Island, N.Y., said the follow-up baby tooth study confuses correlation with causation.

“I consider them ice cream epidemiologists,” he said. “In the summertime, people eat more ice cream than in the winter. In the summertime, more people drown than in the wintertime. Conclusion: ice cream causes drowning. That’s the depth of their science.”

Friedlander, of Washington University, likewise said there are statistical and methodological problems with the study.

He believes there could be value in studying the remaining teeth. But it would be a massive undertaking. Among the many challenges: Tracking down a statistically significant sample of people who donated baby teeth decades ago, especially women who married and changed their names (a reason the 2010 study focused only on men).

“In principle it sounds great,” he said. “But it’s a nontrivial task.”

Mangano has heard the criticism. He agrees more research is needed. But he said the thousands of remaining baby teeth contain valuable information.

“Our study was a first step, certainly not a last step,” he said. “We’ve only done the first step that looked at a relatively small sample of teeth. There’s much much more to be found out from them.”

Harlem Globetrotters - 1 Summer Clinic Registration for St. Louis Area Plus 1 Additional 2015 Tour Ticket Voucher!

Harlem Globetrotters - 1 Summer Clinic Registration for St. Louis Area Plus 1 Additional 2015 Tour Ticket Voucher!

Please Wait…

Please Wait…